|

|

|

|

|

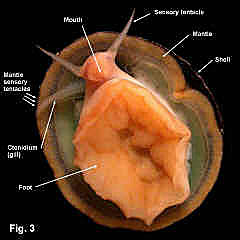

Notoacmea petterdi (Tenison-Woods, 1876) Description: Shell flattened, posterior slope convex, anterior slope straight or slightly convex; widest posteriorly, apex at anterior third. External sculpture of weak, widely spaced, rounded, smooth, radial ribs, sometimes obsolete; frequently eroded. External colouration grey or brown, usually with numerous dark radial bands. Interior with spatula light to dark brown; margin black, or brown with exterior light bands showing through shell; white or blue-grey band between margin and spatula, narrow or absent in juveniles. Size: Up to 25 mm in length, commonly 12-15 mm. Distribution: Endemic to Australia: Noosa Heads, Queensland, to eastern SA, and Tasmania. Habitat: This species lives on vertical and sloping rock surfaces and the undersides of overhangs, at high tide level and above, on exposed and moderately exposed coasts. The animals are inactive when the tide is low or the weather warm, moving about to feed when the tide is high, the seas rough or the weather is rainy. It lives up to 1.8 metres above high tide level, in an environment that only occasionally receives spray from the waves, and is subject to desiccation from wind and sun. Sexes are separate, with eggs and sperm being broadcast into the sea. Anderson (1966) studied reproduction in the laboratory, finding that after fertilisation, eggs develop into trochophore larvae after 16 hours, and then over a period of 30 hours into veliger larvae. Settlement then occurs with alternating crawling and swimming over eight days. Feeding does not begin until settlement is permanent. Two studies have been conducted into the life history of this species. Parry (1982) studied the population at San Remo in central Victoria, and Creese (1980a, 1981) studied populations at Cape Banks in Botany Bay and Barrenjoey in Broken Bay, NSW. Both researchers found that a single spawning occurs in May or June. Larvae are washed up onto the shore depending on variation of wind, tides and waves; there is some evidence that they settle preferentially in the habitat occupied by the adults. Exactly what happens immediately after settlement is not known, but from when the animals are identifiable, at a few millimetres in size and within a month of settlement, they take up a fixed homing position on the shore. The home position may be marked by a depression in the rock, apparently allowing the animal to seal closely to the surface to prevent water loss. Feeding excursions are made from the home site. The food of this species is the film of microalgae on the rock surface, not apparent to the naked eye. The density of limpets on the shore is largely dependent on where the larvae established their home site, as they do not spread out to areas of greater food supply once established. At lower levels on the shore densities are higher and growth is slower as food supply per animal is lower. Larvae that accidentally settle higher on the shore have a larger food supply per individual, and growth may be faster and mortality lower under normal circumstances; however, they are subject to extreme climatic events, such as hot summers. On average, the animals higher on the shore are larger than those at lower levels. This species is relatively slow growing but long lived. In the populations studied by Creese and Parry it reached, on average, a size of 10 mm at one year, and about 17 mm at 10 years. The maximum size of the species is 25 mm, so either these are aged well over 10 years, or they have lived in an area of abundant food supply. While Parry found that there was minor predation by oystercatchers, most mortality is caused by lack of food, due to high population density low on the shore or periods of hot, dry weather high on the shore. Comparison: Juveniles of this species may be confused with dark coloured specimens of N. flammea. They are difficult to separate, but can be distinguished by external sculpture if the shells are not eroded. More useful is the difference in habitat; N. flammea lives ion the lower intertidal, while N. petterdi lives at and above the high tide level. Fig. 1 Long Reef, Collaroy, NSW (C.077363) Fig. 2 a. McMasters Beach, NSW (C.090670) b. Noosa Heads, Queensland (C.090679) Fig. 3 Live animal. Barrenjoey, Pittwater, NSW (DLB5092) |